We all decide to take up new hobbies and activities from time to time. And when we do, most of us reach out to the associated communities to learn all about the subject in question. Trolling online forums, watching video guides, reading publications, and engaging with experts in the field. Inquiring from others about all of the do’s and don’ts and how-to’s.

Every photography newcomer starts with a seemingly innocent question; “What camera should I get?”. This seems like a very logical beginning. To make a photograph, you need the equipment. The right equipment. And a camera is the very foundation of this process. It is but with this simple question that they begin to realize how loaded this question actually is.

That is because there are more camera types and brands than there are shoes in a celebrity’s closet. There is a plethora of other sizes and formats. Medium format like 645 or 6×7 systems, large format systems, miniature formats like 110, APS, and 35mm (yes 35mm is classified as a miniature format) . And each of these available in different camera forms like the popular Single Lens Reflexes (SLRs), rangefinders, view cameras, folders, and Twin-Lens Reflexes (TLR) only to name a few. All of which can be bewildering to someone not at all familiar to photography.

Naturally with such an assortment to sift through, there are no shortage of photography websites and blogs replete with recommendations for cameras for beginners or best film cameras for students. Often these guides prominently feature a camera that I have come to loathe. It is not that it is a terrible camera. Ironically it is the camera that began my journey into photography. But it was not until I started learning about and exploring other systems that I really began to understand how cameras and the photographic process works.

The camera is the ubiquitous Canon AE-1. Produced from 1976 to 1984, the AE-1 was the first SLR to sell over one-million units. With an aggressive advertising campaign, these Canons were snapped up by the public and today these cameras can be found for a swan song. The silhouette of the AE-1 is instantly recognizable, even by those not in the photographic community.

The AE-1 made photographic history not because it had a myriad of never before seen features or a spec sheet that would shame even an exotic automobile of the era. It’s place in history isn’t in what this camera could do; but in how the camera did it. Canon was the first to employ the use of computer microprocessors and create an electronically controlled camera when, at the time, most cameras were mechanical with little (if any) electronics inside at all. Along with the greater use of plastics, this reduced complexity and made the camera more economical and more consistent to manufacture.

This is the primary reason this camera makes a top pick on so many photography blogs. The camera is readily available and, because it uses a dead lens mount, it is available at low cost for a unit in clean good working order. Let’s not also forget that those FD mount lenses are often really good and also quite affordable. So why, you might ask, would I not recommend this camera to beginners? Because the camera does not function in a way that easily translates to how photography is taught.

Photography is traditionally taught with understanding exposure and the roles that aperture, shutter speed, and ISO play in the creation of a photograph; both technically and artistically. The AE-1, while serviceable when used manually, is not designed to best be used with full manual control. A prerequisite of a camera brought into any beginning photography course. It was designed to be used in its shutter priority auto exposure mode. So, why would Canon build a camera utilizing the most advanced microprocessors and circuitry of the time to be used without benefit to the photographer? This if why simple mechanical cameras, such as the ever-present Pentax K1000, with their match-needle style metering, are approachable and ideal for teaching beginners.

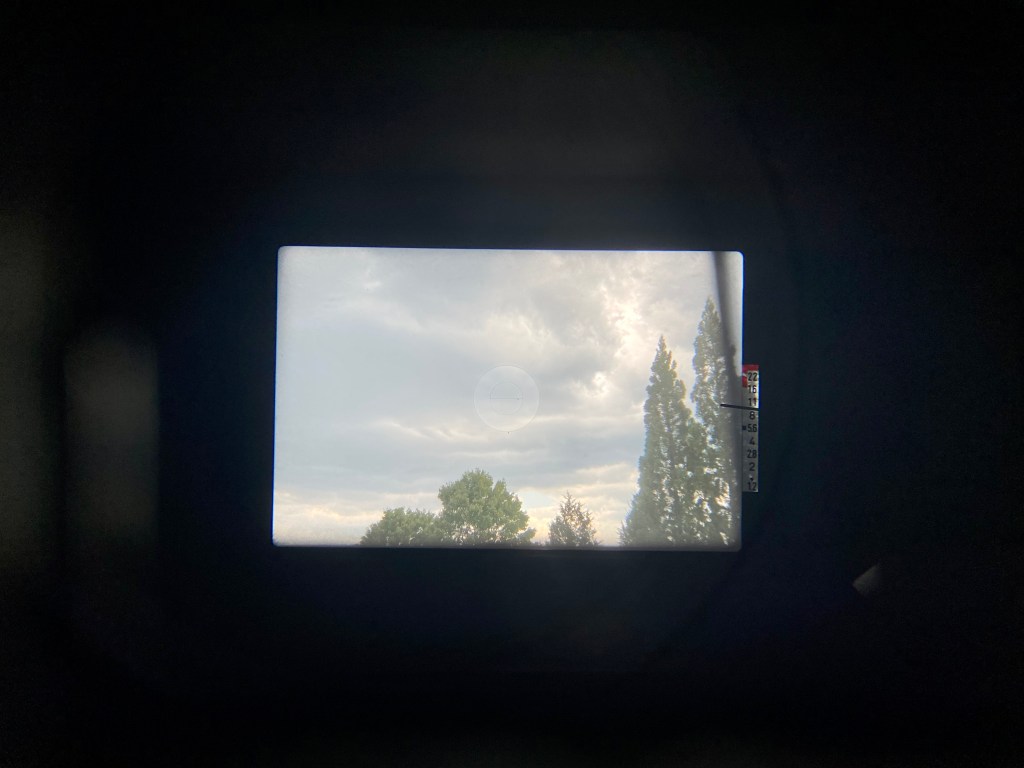

With these cameras, you hold it up to your eye and adjust the shutter speed and/ or the lens aperture so that a needle (often seen in the viewfinder) aligns in the center of a scale or on another needle (or flag). Some newer cameras use a series of LEDs. An ideal exposure is achieved when the center LED is illuminated. It is quick, simple, and nearly self explanatory. I can give almost anyone a camera and say turn this and this until these needles match up. There is not much guess work or calculation involved in just getting a good basic exposure.

The Canon AE-1 on the other hand, you select a shutter speed, half-press the shutter button to activate the meter. The needle in the viewfinder points on a scale of aperture values, indicating the aperture the camera recommends for the best exposure. You then need to select that aperture by taking the camera away from your eye to look at the aperture ring on the lens. After turning the ring to the desired setting, you look through the viewfinder again, recheck metering and focus, and take the picture. Keep in mind the entire time you have the shutter button pressed, an annoying red “M” is blinking in the viewfinder at the top of the meter. Almost to say “STOP!! Are you sure you know what you’re doing? Don’t you want me to figure this out for you?” The AE-1 only ever shows you the aperture that the camera will use (in auto mode) or recommends you using (in manual mode). There is no indication in the viewfinder of which shutter speed or aperture you have selected. Only the blinking “M” to remind you that the lens aperture is not set on “A” or another blinking LED in the bottom when severe over or under exposure results

To be fair, there are other cameras, such as that omnipresent K1000, that also lack any display of current shutter speed or aperture settings. But to know that, according to the camera’s meter, I have things set to obtain a well exposed image is as simple as looking at the meter needle position. Near center? Great! It is that easy. The needle gives a quick visual representation of exposure value. When using the AE-1’s preferred auto mode, as long as there isn’t a blinking LED, then you will get a proper exposure. In manual mode however, the needle does not represent the exposure you will get. It will only remind you of what lens aperture you should use. If you have an aperture set that will over or under expose an image, the meter in the viewfinder will not tell you any different.

The AE-1 was the first SLR camera I ever used. I took a lot of images with that camera. Most of which are unmemorable snapshots. I did not know how to get the most out of that camera. The measurement of aperture in particular was confusing to get used to. Despite reading the camera’s manual multiple times, it was not until I began reading other photography sources and using other cameras and camera systems that I began to grasp the creative implications of aperture choice. In short, other cameras taught me how the AE-1 worked and this is why I recommend other cameras over the AE-1 as a beginner photographer’s camera of choice.

Leave a comment